Ozone: Good Up High, Bad Nearby

Ozone is a gas that forms in the atmosphere when 3 atoms of oxygen are combined (03). It is not emitted directly into the air, but at ground level is created by a chemical reaction between oxides of nitrogen (NOx), and volatile organic compounds (VOC) in the presence of sunlight. Ozone has the same chemical structure whether it occurs high above the earth or at ground level and can be 'good' or 'bad,' depending on its location in the atmosphere. Ozone occurs in two layers of the atmosphere. The layer surrounding the earth's surface is the troposphere. Here, ground-level or 'bad' ozone is an air pollutant that damages human health, vegetation, and many common materials. It is a key ingredient of urban smog. The troposphere extends to a level about 10 miles up, where it meets the second layer, the stratosphere. The stratospheric or 'good' ozone layer extends upward from about 10 to 30 miles and protects life on earth from the sun's harmful ultraviolet rays (UV-b).

Ozone is a gas that forms in the atmosphere when 3 atoms of oxygen are combined (03). It is not emitted directly into the air, but at ground level is created by a chemical reaction between oxides of nitrogen (NOx), and volatile organic compounds (VOC) in the presence of sunlight. Ozone has the same chemical structure whether it occurs high above the earth or at ground level and can be 'good' or 'bad,' depending on its location in the atmosphere. Ozone occurs in two layers of the atmosphere. The layer surrounding the earth's surface is the troposphere. Here, ground-level or 'bad' ozone is an air pollutant that damages human health, vegetation, and many common materials. It is a key ingredient of urban smog. The troposphere extends to a level about 10 miles up, where it meets the second layer, the stratosphere. The stratospheric or 'good' ozone layer extends upward from about 10 to 30 miles and protects life on earth from the sun's harmful ultraviolet rays (UV-b).

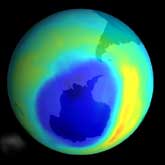

Ozone occurs naturally in the stratosphere and is produced and destroyed at a constant rate. But this 'good' ozone is gradually being destroyed by manmade chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), halons, and other ozone depleting substances (used in coolants, foaming agents, fire extinguishers, and solvents). These ozone depleting substances degrade slowly and can remain intact for many years as they move through the troposphere until they reach the stratosphere. There they are broken down by the intensity of the sun's ultraviolet rays and release chlorine and bromine molecules, which destroy 'good' ozone. One chlorine or bromine molecule can destroy 100,000 ozone molecules, causing ozone to disappear much faster than nature can replace it.

As the stratospheric ozone layer is depleted, higher UV-b levels reach the earth's surface. Increased UV-b can lead to more cases of skin cancer, cataracts, and impaired immune systems. Damage to UV-b sensitive crops, such as soybeans, reduces yield. High altitude ozone depletion is suspected to cause decreases in phytoplankton, a plant that grows in the ocean. Phytoplankton is an important link in the marine food chain and, therefore, food populations could decline. Because plants 'breathe in' carbon dioxide and 'breathe out' oxygen, carbon dioxide levels in the air could also increase. Increased UV-b radiation can be instrumental in forming more ground-level or 'bad' ozone. The Montreal Protocol, a series of international agreements on the reduction and eventual elimination of production and use of ozone depleting substances, became effective in 1989. Currently, 160 countries participate in the Protocol. Efforts will result in recovery of the ozone layer in about 50 years.